https://revues.mshparisnord.fr/filigrane/index.php?id=1136

Stelios Giannoulakis 2021

Abstract:

This paper attempts to analyze connections between the urban sound environment and electroacoustic–acousmatic music composition. Having chosen recorded sound as the main material of my sonic art, I sometimes use unprocessed sound and drive the composition forward by editing, according to the locally emerging myth. Alternatively, I might use recorded sound as a malleable material I can warp to the extreme. ‘Real world’ sound has a certain power on the mind of the listener and so have processes of its transformation, playing with degrees of recognizability and laying out idiosyncratic dream-scapes to follow and explore. The urban soundscape, appreciated as a city dweller’s natural sonic environment, significantly informs my creative processes. As continuous exposition to certain sounds tends to redefine the archetypes that govern the way sound is evaluated as art, the meaning and cultural significance of noise changes. Exploring the concepts of noise, soundscape and creative field-recording as a listener, engineer, sound designer, and composer, I approach mechanisms that allow the sounds of everyday life to participate in the development of a compositional language connected with fundamental elements of musical tradition and directly dependent on the ways sound might be appraised.

Keywords: Creative Field Recording, Urban Soundscape, Noise, Composition, Acousmatic, Sonic Art, Relationships

1. Introduction

Since the late 18th century, the world has acquired a lot of new sounds due to technological developments and increasing urbanization. These sounds gradually established themselves as part of the generic environment, demonstrating unusual intensities and novel timbral qualities. Impressive sounds, possibly ascertained as hostile or just tiring due to their unnatural rigidity, their loudness, their overwhelming functional persistence. Characterizing this sonic reality, the word noise became particularly relevant. At the same time, continuous exposure to such sounds has been, and still is, gradually changing human response to the phenomenon of sound in general. As a result, there is a gradual shift in the archetypes and the mental processes that guide the interpretation of sound as art.

What is music and how it relates to non-musical sound has always been a perplexing and thorny subject, due to the complex biological, social, economic, aesthetic, and philosophical extensions of the functions of sound in human life. It is a subject for endless theoretical and practical discourse and an important parameter in my own creative approach. In 1837 the poet-philosopher Henry D. Thoreau wrote in his journal:1 ‘Nature does not make noise. The howling storm, the rustling leaf, the rain slowly falling are not a nuisance, they present a substantial and indecipherable harmony.’ One might observe here that Thoreau is extending a welcoming hand towards chaotic and harsh sounds of nature and not towards the sounds brought about by the industrial revolution. Jeff Titon2 explores this tension in Thoreau’s sound-related insights. Nevertheless, as the cultural connotations of the words noise and harmony in the passage above get inverted, extending appreciative attention to complex, chaotic, or aggressive sound, language bends to outline a vivid interplay between value systems. A call for audible qualities to be reassessed, following the fascination of a sensitive ear with sounds of questionable cultural status.

The social standing of noise is constantly re-evaluated, with the words noise and music participating in a constant dialectic dance. The noise instruments of the Futurists, big-city sound as manifested in Edgard Varèse’s seminal works, the sonic masses manipulated by Iannis Xenakis, the radical presentation of random sound as music by John Cage, the deep involvement of Musique Concrète–Acousmatic Music with the sound object as musical material and of course, the use of any type of sonic extreme in popular genres, all these are recent points on a continuous cultural trajectory, within and across a range of creative cannons. Over the centuries, creators and thinkers developing strategies for the construction of musical meaning have been cultivating modes of sonic appreciation that widen musical thought to the point of embracing any possible sound. Even sounds that may be disturbing or otherwise unwanted find a prestigious place within contemporary music. The dimensions and textures of the subjective notion of noise are changing over time periods and the relationship between the notions of noise and music reflects cultural dynamics and precedes social changes.

A more detailed study of the development of contemporary music is beyond the scope of this text, so I settle for a few vivid references. For example, the following phrase frequently attributed to Brian Eno (actually said by painter Tom Phillips, at a common interview in 1998): ‘John Cage made you realize that there wasn’t a thing called noise, it was just music you hadn’t appreciated’. This clever aphorism, teasingly winking to audiences and critics, aptly defines the landscape inherited by a contemporary musical aesthetic. Beyond the need for a deeper examination of ideas such as noise and music, not to mention the notions of existence or appreciation, it is clear that the subjective criterion of the listener-creator has a huge space in which to wander around. A space with hidden treasures and perhaps challenges. However, this criterion is expected to support a lot of weight. For the average person, the relationship between noise and music is neither clear nor peaceful. For the experimental composer, though, it defines a wonderful playground.

As a composer of contemporary music, I enjoy a particular affinity to the sound of the city. The urban sound environment plays a major role in the development of my artistic language, and within my work, I explore possible relationships between the complex system of everyday sound and something we might call music. Most of my works use the language of electroacoustic music7 in an acousmatic context, in the sense that the relationship between the sounds and what we might perceive as their source and cause is constantly modulated within the piece, as part of the musical development. In the following sections I will attempt to articulate a compositional mindset that allows everyday city sound, the city soundscape, one might say, to participate in the development of a sound poetic. Sonic creation with aesthetic and emotional impact that is inspired by and realized with a system of sounds that could be referred to as the noise of urban soundscape.

But, before analyzing how the city sonic environment feeds into my compositional strategies, themes and techniques, I need to share some thoughts on the word noise and its semantic ambiguity, as well as on the word soundscape, as it is not obvious what it implies either. I shall start with the latter.

2. On soundscape – metaphors and shifts

The sound of the city is characterized by high density, variety and richness, contains strong contrasts and is associated with a vast array of symbols and associations. It is literally the soundtrack of our culture, stemming from everyday materials, devices, people, relationships, processes and systems. Machines on streets and inside houses, materials, tools, construction, furniture, doors, reverberations and other architectural elements, voices, crowds, footsteps and wheels on various surfaces, atmospheres, silences, clear tones, signals, media and stylized speech, random music recorded or live, and whatever else may be. All these sound sources function as a system along with parks, hills and beaches, within and around the city. A sensitive and complex evolving sound ecosystem, worthy of active listening and deep study. With its own anthropophony, biophony and geophony, the big city sound environment defines in part a contemporary sonic nature.

Alas, this angle seems to rub against the most widespread paradigm of thinking about the urban soundscape. The term soundscape is defined by ISO as an ‘acoustic environment as perceived, experienced, and/or understood by people, in context’, and is loosely used to describe any set of sounds, as long as they can be heard as an ‘acoustic environment’, with physical or imaginary materiality. Radicci asserts that the term has ‘proven robust enough to withstand the critique and is still widely used’. Ingold argues against the term. He writes: ‘It is not so much what we perceive as what we perceive in […] sound and light, are infusions of the medium in which we find our being and through which we move’.For Ingold, the embodiment and emplacement of sound as implied by the term soundscape, can remove us from the true experience of sonic flow.

It seems though that more is at stake, so to speak. Murray Schafer made the term popular in The Soundscape – Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World. Schafer analyses a large array of sound types that form part of the global soundscape, the audible part of the contemporary world, I should say, to follow Ingold’s rationale. Schafer meticulously traces the evolutionary steps towards a contemporary sonic environment, concentrates on the accompanying rise in ambient noise levels, and lays out an ethic of acoustic design, a ‘set of principles to be employed in adjudicating and improving soundscapes’ that may be ‘confused and erratic’, perhaps preserving important soundmarks, towards an ideal soniferous garden.

I am not comfortable with the metaphor of a managed garden as the overarching paradigm for the sound we live in. I prefer to think of it as a wild forest, where one may wander around admiring, foraging, experiencing a system one cannot control, other than within a critical range of personal responsibility, and perhaps suffering because of that. One might die in the jungle, succumbing by hardship, bitten by animals, consumed by fungi. Does this mean that the jungle is confused or erratic and needs to be managed? If we live in a jungle how much do we want to manage it? Or, to put it differently, thinking along Schafer’s tuning metaphor, I would say that the world has many tunings, like the guitar or the synthesizer, and these include various functions of noise. The benefit or harm brought to us by the world’s sound is not something we can generalize with broad metaphorical strokes.

Eleanor Ratcliffe writes: ‘Cities are inevitably noisy, but there are also many individual desirable sounds embedded within them’, consequently suggesting that certain sound types in cities might be pleasant, relaxing, restorative or potentially psychologically beneficial, in contrast to sounds that have opposite effects. This may very well make perfect sense from an environmental psychologist’s point of view, but alas, for a composer of sonic art, the listening paradigm may be quite different. I don’t believe that making music with urban sounds deserves to be thought of as cooking with toxic garbage, or as sculpting with excrement. As established earlier, noise as related to disturbing sound has a much more complex function for human culture. But what are we talking about, in the first place?

3. A word with issues – creative perspectives

Of course, the word noise does not refer exclusively to sounds of the city or the sounds of civilization. However, such sounds tend to get referred to as the main perpetrators of ‘noise’ today, especially in contrast to everything that could be thought of as ‘not-noise’. The preoccupation of ethics and aesthetics with noise intensified along the development of modern technology and due to the daily exposure of people to particular sound types within cities. The city is truly a theater of noise, as however is nature. The sea, the wind, insects, a landslide, a storm, cars, horns, or even music itself may or may not be perceived as noise, after all. This word has more than one interpretation, interconnected but not necessarily complementary. These interpretations attempt to coexist but ultimately clash with each other, presenting an interesting problem and causing the word to essentially fail – or just have great philosophical and poetic interest, one might say.

Marie S. Thompson analyzes this problematic in Beyond Unwanted Sound: Noise, Affect and Aesthetic Moralism. If we look at the technical meaning of the word, as relating to physics or engineering, noise means sound (or information in general) without periodicity, with high entropy and dense spectrum. This is what Thompson refers to as object-oriented noise. Noise, in that sense, exists everywhere. The majority of natural sound consists of noise, caused by the impact or friction between materials. Spectral analysis of the sounds emitted by acoustic musical instruments, for example, shows that particularly at the onset of each tone there is noise, due to the chaotic phenomena accompanying excitation. If we detract this noisy onset, the sonic qualities we enjoy from those instruments are dramatically altered. For this reason we need controlled noise generation and stochastic methods, if we want to convincingly reproduce the sound of physical bodies using sound synthesis techniques. Synthesizers use noise as a valuable source for the creation of all sorts of sounds.

The word noise is used to mean much more. We have an interpretation related to information transmission or signal isolation. Within a transmission channel, any signal that might be of some interest is accompanied by noise (chaotic component added by the channel). This is caused by imperfections of the system’s parts, by stochastic behaviors due to the nature of materials and by interference. In this case, the noise is something we do not need, something we try to eliminate so that our signal is healthy and useful. The less noise there is, the higher the signal to noise ratio, the better our system. So, from the observation that part of our channel is taken up by useless noise, as a technical byproduct, we end up in everyday speech calling noise something that hinders our efforts to access pure information, something that interferes with a desired experience. Through continuous generalization of the above signification, noise ends up meaning annoying sound, therefore something subjective and morally loaded. Thompson refers to this as subject-oriented noise.

I find the investigation of this concept particularly interesting because it relates to how we think about sound in general and holds a key to understanding emotional functions of sound and music perception. Hearing helps humans understand what is going on around them, so inevitably some sounds have a higher capacity to cause negative emotion. Of course, sound serves communication through speech and this is a very important function of the auditory mechanism. Consecutively, sonic events attract human interest on many levels, as they might mean something else besides danger, something important and useful, maybe pleasurable or even necessary. Part of the pleasure we can experience through the sense of hearing, we get from what we call the art of music. If we see listeners themselves as creators, we might call music any audio experience from which we are capable of extracting acoustic enjoyment. The audio experience which we do not enjoy we might characterize as noise, especially if it lasts for longer, disrupting our normality. In everyday speech, this word is often used to signify sonic pollution and sonic violence, consequently something widely unacceptable, something we need to control or eradicate. It is true that part of sonic pollution is in fact noise, with the technical meaning of the word. This fact however does not justify the characterization of any annoying sound or of all annoying sounds as ‘noise’. Sonic violence is primarily applied through the use of sound which is not noise but loud music (Beethoven in the film Clockwork Orange, an after-hours party harming the neighbors etc.) or pure tones (anti-theft sirens, crowd control devices, etc.).

For me, the main problem with the word noise comes from the fact that generally speaking, it is of higher importance to avoid non-consensual sonic violence, than to enjoy interesting sounds. Sonic violence can be something so toxic and dangerous that for the collective mind, the negative meaning of the word tends to supersede any other. Sound has power and meaning, and its production can be easily misaligned, in any given situation. Delicate dynamic systems, from individual psychologies to whole ecologies, can be seriously destabilized by irresponsible sound emissions. Soundscape ecology and Schafer himself, focus on the negative impact of human sonic activity for obvious reasons. Indeed, we cannot ignore the anomaly of a techno-blasting beach bar or of a loud construction project in a natural resort, for example. Thoughtless chatter in a library? A two-stroke engine motorbike with no exhaust on quiet streets? For how long can one endure the hammering and drilling sounds from the floor above? How tolerable can a drummer practicing next door to the writer be? This is why there are customs and laws concerning sound, a whole audio-related social construct, written or not. Individuals, public venues, workspaces or vehicles, all need to adhere to rules regulating their sonic behavior. Irresponsible sound generates suffering. This is how the idea of managing the soundscape seems to make sense.

Nevertheless, someone can consciously choose to hear noise textures in order to relax or to partake in an incredibly noisy music event for the purpose of ecstatic methexis. Young parents get to discover this paradox trying to get babies to sleep. Teenagers, rock musicians and electroacoustic composers alike, often tax their auditory apparatus willingly, as they enjoy the rush of immersion into loud edgy sound. The music celebrated by some is the noise sickening others. Health concerns aside, it is not exactly noise what we want to discourage or control, perhaps even prohibit. A Day Against Noise should actually be Against Sonic Pollution or Against Sonic Violence.

Consider the words doodle or smudge for painting for example or black, yellow, or white for humans. Every time a word related to the objective nature of a phenomenon is permanently loaded with subjective moral weight, by connotation or metaphor, prejudice is implied and encouraged. It is a function of language. We may also consider simple words like hard, cold, small, rough, and countless others. Within the abstractions and significations of the semiotic web of language, we should be mindful of context and moral generalization. The operation of a word can easily be distorted and the related phenomenon oversimplified, rendering the evaluation of subtle shades and qualities impossible. In general, this is something we do not want. When we decide to make use of loaded oversimplification, for rhetorical or poetic purposes, there is always a conceptual price to pay. This is why many composers who use ‘noise’ elements extensively in their work avoid this term, though much of this music is incorporated by third parties into a broad genre ironically called noise music.

Within the term noise music, noise is consciously, at least in part, implied to be a nuisance. Indeed, the negatively charged meaning of noise, often aided by high volume and strong symbolism, can clearly supply aesthetic function within musical contexts. In general, the use of annoyance for aesthetic enjoyment, within the context of art, has been widespread and philosophically traced. Writing about this phenomenon, Vassilis Raphaelides mentions among others, Jean-Marie Guyau, Roland Barthes and Jorge Luis Borges. Paul Hegarty mentions Jean Baudrillard, Georges Bataille and Theodor Adorno. As art integrates us into a whole, we enjoy the clashes between contrasting meanings, the pleasure-giving rifts, the grandeur in transcending boundaries within the unifying condition structure of a captivating experience.

This dimension of sonic edge enables the untrained ear to approach works by composers such as Xenakis, Vaggione or Smalley, and brings the wide audience closer to more or less experimental idioms, from Jimy Hendrix and Lou Reed, to Pansonic, Ryoji Ikeda or Merzbow. The narrative, though, will be gradually refined and eventually completely transformed for a listener who appreciates the range, elaborate complexity or delicate qualities offered by creators like the ones just mentioned. Auditory and symbolic provocation has given way to other complex musical functions, as a point of contact for the listener to many ‘noisy’ composers of the past, including Beethoven.

4. The angle of a composer

From the angle of a composer–sound designer, the word noise and its significations seem indispensable. The negative implication is something that can be taken out of the main focus, but as a strong cultural trend it cannot be ignored. I see a strong creative potential within the semantic tension, and my work leverages this dynamic for compositional affect, drawing from the city as a theater of noise (any interpretation of the word being relevant here). I use ‘noise’ all the time and will give more examples further on, describing my techniques and strategies in more detail.

Thompson writes: ‘If noise is anything it is “both-and”: it is both surprising and banal; both spectacular and unremarkable; both obvious and unknown’. Within musical contexts, the urban sonic world does not necessarily carry something romantic, picturesque, violent, extreme or revolutionary, not even something in itself interesting or noteworthy. The evocative potential of sound experienced as art hinges on the artist’s and listener’s inspired combination and framing. With that in mind, I use the sounds of the city neither as rebellion nor as attraction. Recognizing these two functions, among many others in sonic art, I see the city as an endless source of audio material. At the same time, it is a cultural system of evolving aesthetic trends, an unlimited source of inspiration for my compositional approach, an extensive field of creative exploration.

With a disposition toward discovering and appreciating my sonic environment, I listen freely and creatively. Without prejudice, if possible, I try to enjoy the complex sounds of the world, be they random events or purposefully crafted sonic statements, feeling free to tune my attention to a wide range of sonic intensities and densities. I develop my ability to value complex, chaotic and possibly disturbing sounds, something akin to a ‘noise’ aesthetic. Of course, there are preferences, time or case appropriateness, fatigue thresholds, focus, boredom, addiction or excess, the thirst for adventure in contrast perhaps to a need for safety. These and numerous other important and ever-changing parameters always modulate and inform my listening experience. Having said that, in the grand scheme of things, I listen inventively for the nuance behind the veil, the obfuscation that hints towards importance, the fragile among the powerful, the unique within the ordinary. I also listen for the extremes that balance out, the intensities that counteract. I welcome waves of acoustic energy that may enchant the ephemeral carpet of consciousness and make it fly, reinforced by complex emotion.

The noise of the world carries stories. Following the sonic flow at the city’s concert, we hear threads of textures and gestures intertwine and inter-mutate. As sound surrounds and guides us according to our listening intentions, we become the creators of our own experience, by directing our attention and choosing points and paths. The sonic trajectories drawn by the natural movement of people and machines unfold structure, in small, medium and large time scales. Within this structure, musical motives can be followed, along processes of detailed articulation and teleological development. This notion of purpose, as imposed on the sounding physical materials, often generates a sense of purpose carried within the sonic structure itself, in musical or compositional terms, a phenomenon that is a joy to explore both as listener and composer. And as the waves of sonic and conceptual activity combine, we can prime expectations, investigate atmospheres and contexts, observe references in discourse, and experience cadence-led closures.

As a trained listener living in a metropolis, I find this mindset indispensable for keeping one’s sanity. And as a city-dwelling composer of contemporary sonic art, I find this disposition valuable for its creative potential, so I leverage it in my works. Urban sonic aspects find their way into my pieces, pure and re-framed, or distilled and highly stylized. Turning urban sound into musical meaning, through the manipulation of time and the articulation of perceptual choices and conditions, is a main point in pieces such as Big Village Dynamics, Transference, Athens Noise Orchestra or Athens Modular Soundscapes. Also, works like The Way In, The Maze, Chaotic Lucidity, Rites of Passage or Fragmental contain snapshots and patterns of urban sound appreciation, as important elements in their development. At the same time, other pieces that don’t rely on the urban sound world, such as The Sonic Alchemist, Distinct Phases or Particle Chant, are definitely inspired by the sonic activity, timbral contrasts and structural models offered by a big city.

I often articulate the noise element and thus the perceived materiality of sound objects, as a musical parameter. Particular spectral cues can relate to exact notions of physical excitation. So, by carefully controlling noise processing parameters, I can induce connotations of excitation agency or material quality in abstract sound streams. As ambient noise is almost always part of a real-life outdoor sound scene, by introducing the right type of noise at the right time I can play with a sense of ‘outside’ vs ‘inside’ dynamically, crafting transitions and musical interactions. Sculpting noise, I may also create discourse between perceived notions of background and foreground or environment and presence. For example, in The Way In, around 3:15, the end of a noise-filled section leads into the beginning of the next, where the total absence of ambiance creates a contrasting sonic landscape and a strong symbolic connection. In the same piece, around 12:25, the sound of a voice is transformed into some kind of a forest, and towards the end the ‘forest’ is gradually sucked into a held note.

The information-related meaning of the word noise connects with a certain problematic that goes far beyond the technical and offers a wide field of creative considerations. By intentionally randomizing or obstructing the impression of some recognizable sonic presence and interfering with the clarity of the sonic thread followed by the listener, I might amplify patterns of tension and release, as well as drive musical form. Of course, this idea of playing with the listener’s processes of expectation and reward is ancient, a powerful storytelling tool. Following the information-noise paradigm, I can modulate the apparent nature of a perceived sonic agent, responsible for the obstruction or complication. Modulation of focus and ‘noise’ character turns the noisy channel itself into a musical parameter, or a vector of symbolism, with the power to hide or to reveal something musically crucial. In The Maze, for example, this technique allows me to musically realize the idea of wandering through a weird magical maze, especially after about 8:30 as tension rises towards the finale.

5. Creative field recording

Exploring my sonic environment, I record. In the field. Hildegard Westerkamp in ‘The Microphone Ear: Field Recording the Soundscape’, describes a number of field recording approaches, and more importantly a high degree of audio awareness, while exploring and capturing the sound of the environment.

Field recording is the term used for recording audio outside a recording studio, and applies to recordings of both natural and human-produced sounds. My own field recording and found sound study practices can be seen as the production of resources for their instrumentalization, within the aesthetic parameters of Electroacoustic Music. This angle, although proximate, does not totally align with the body of literature around related sonic methodology. I diplomatically say that I creatively use techniques of field recording but must also outline an argument for the applicability of the term to my type of approach. The act of recording is always imposing additional parameters onto the sound that is captured, from the selection of place and time to the choice of microphones and focus, to the conceptual framing of these choices. The nature of the captured sonic information relies equally on what is sounding and on how it has been recorded. If the goal is a faithful reproduction of what I can hear, I may strive to capture it in the most transparent way possible. As a composer though, I tend to think creatively about the ways my act of recording shapes the sounds experienced in the field. This creative freedom may lead to a recording that is very different from what the related environment sounds like to a naked ear. I do not exactly record the urban soundscape. I record within it, creatively capturing found sound in the field.

My recording in the city sometimes captures sound walks, sometimes sonic scenes or sound objects of interest, possibly in connection with a project or circumstance. Recordings can take place at different times, capturing specific or just different versions of audio, perhaps at the same place. The microphone may be stationary or in other cases purposefully moving, for example gradually from or towards some detail, rotating, or transitioning from one source to another. From simple adjustments to choreographed motions, microphone manipulation has a huge impact on the captured sound and while recording I have to constantly make decisions of technical and aesthetic nature in relation to the desired result. Invariably, exhaustive handheld-microphone soundscape exploration, often with superhuman hearing through headphones, completes at least one compulsive creative cycle, for someone who is fascinated by sound as art material.

Through this process I realized two obvious truths:

a) I will never be able to collect all sounds. There will always be something different, interesting or unique that inspires wonder but is lost, escaping a recording. Just like shooting with a camera, or collecting stones on a beach. Life and noteworthy experience are far broader than what I might capture in my collection, no matter how hard I obsess about them. Most amazing things will be fleeting glimpses during a bumpy ride, for which I am thankful. Exercising attention and absorbing what I can or what I need, I feel like a hunter-gatherer of sound.

b) Sound will always be available for exploration or collection. Of course, some urban sounds will change or disappear in the future, they might be already under threat, as is the case with animal or natural environment sounds. In this sense, some urban sounds deserve special attention, in order to be recognized and recorded. I say this from the point of a collector or preserver, thinking for example of outdated technologies, buildings to be demolished or soundscapes of old workshops and neighborhoods. Most importantly for today’s noise theater, one of the main actors, internal combustion engines, will soon be eclipsed with the advent of electric vehicles. As the environment and habits change, the soundscape changes. This of course is a subject for acoustic ecology and for anyone concerned with evolving anthropogenic sound ecosystems. While having these thoughts, however, it is very difficult to imagine a condition with nothing available to produce sound. Some sounds may become extinct, but the various sound families will continue to be represented for a long time, perhaps until some huge catastrophe changes everything radically.

I may handle physical elements of the environment as sound instruments in the field, looking for specific sound families and sequences, experimenting with materials and ways to excite them. Thus, the analogy of hunter-gatherer for sound can be extended to that of a farmer. This relates to the practice of Foley Art or the sound production practices of Musique Concrète. Components of urban sound, such as structures, metals, plastics, glass, containers, tools, small and large appliances, musical instruments and various other sound-making contraptions, may be incorporated into artificial scenes, small controlled environments with particular sonic properties. This way I can design and perform city-inspired sound and musical form in controlled ways. I used such material and its references to audible realities in Zraaamm!!!, The Maze, The Way In, Chaotic Lucidity, Rites of Passage, and other pieces, for thematic and structural effect within larger sonic palettes.

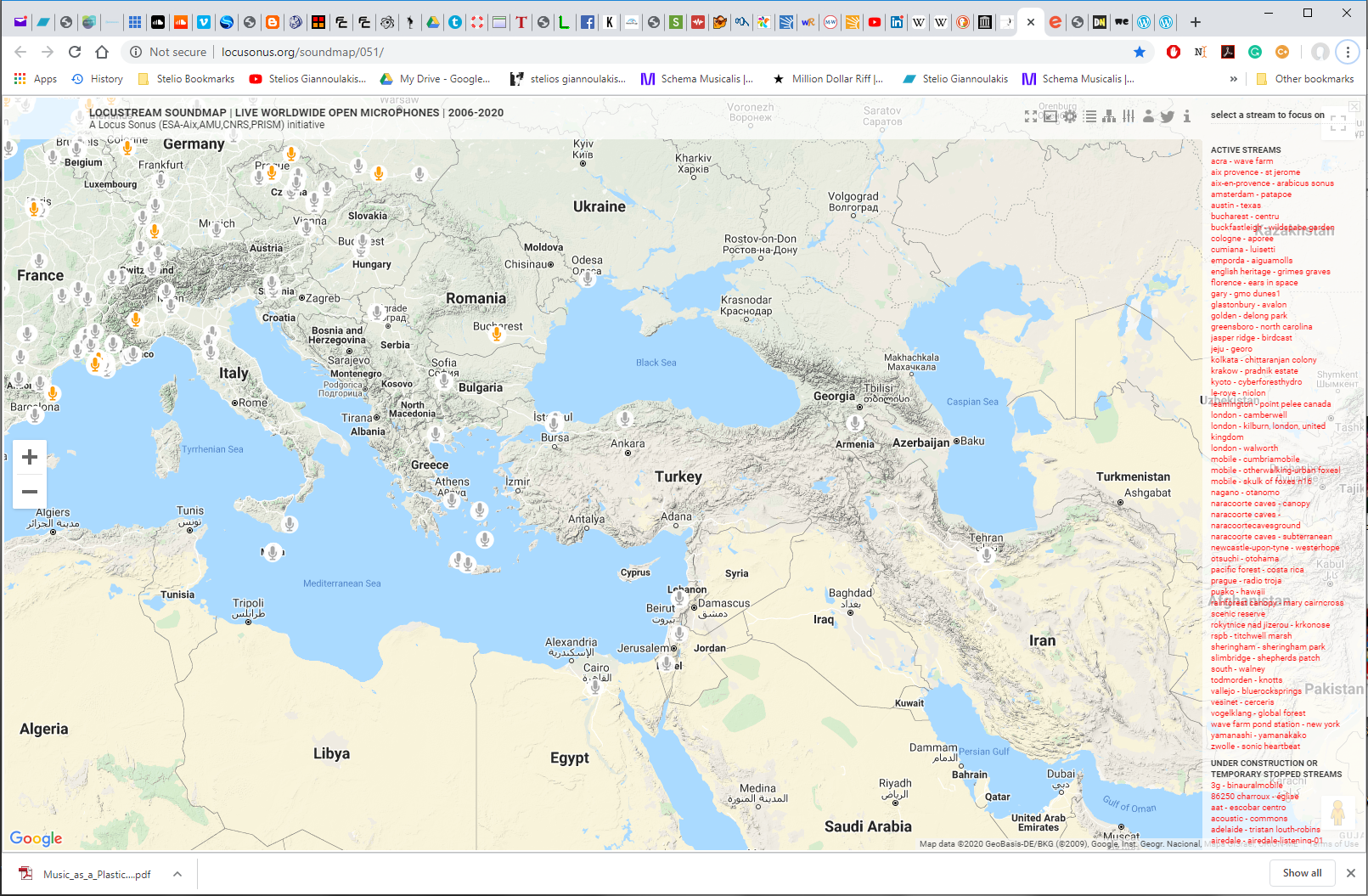

Some more examples: for The Maze I recorded various activities in and around the university building in Bangor, Wales, during the day and late at night. For the piece Rites of Passage, 24 Hours in Passage International I recorded a 24-hour cycle inside a shopping mall in Reims, France, trying to include sonic snapshots from as many elements of the soundscape as possible. For Rainwater I recorded the rain on the metal awning and the gutter of my balcony in Athens, followed by the sounds of the downtown neighborhood after the rain, as could be heard from the balcony. I recorded a series of audio walks in downtown Athens for Big Village Dynamics: Athens Sound Walks. Distorted traffic sounds, captured directly with a camera microphone, provided material for Transference. For Athens Noise Orchestra, I recorded lengthy passages at busy intersections and a central metro station – variably processed versions were then orchestrated, while keeping the timing of the events intact. For Athens Modular Soundscapes I played live electronics along an amplified real-time stereo sound feed from a sixth-floor balcony in Athens city center.

A very special case is the recording of background noise or relative silence, in anticipation of some occurrence. I like to think that the most treasured sound object is silence, with a value that infuses any other sound that comes it its vicinity. This notion informs processes of composition and sound collection alike and holds true while composing with sound objects in a virtual sonic space and while listening, evaluating and foraging in a real-world soundscape. Of course, the word silence, if taken literally, refers to a rare, almost unattainable physical state for anyone not deaf. This is a realization that only adds to the importance of sonic relationships, as the paradigm for sound appreciation within a complex and ever-changing system. I will elaborate on this last idea.

6. Composition and relationships

We may perceive beauty as a potent organic unity, like nature. In terms of art aesthetics, ‘the whole retains its authority over the parts and differences are eroded into complementarities’. This idea can be interpreted as a generalized notion of counterpoint, ‘an economy integrating free and autonomous objects into a totality, through the power of artistic organization’. These notions can be applied to the urban soundscape and will facilitate a creative approach to any complex system. The variety of stimuli in a contemporary urban soundscape is impressive, full of contrasts and interactions. The autonomous is expressed within micro-universes of moving boundaries and as the dividing lines change, elements and groups inter-modulate. The artistic organization is an act of composition, but can also be seen as an act of perception. The general theme that springs from these thoughts for me, and that is explored in various ways in my works, is relationships: between the whole and its parts, between behaviors and conditions, between people and art. A continuing study on unity and transformation, on fusion and dialectic.

As I compose with sound, I explore this overarching concept from many different angles. For each piece I sense, acknowledge, adopt, or serve a more specific theme, possibly just a temporary working one. The sound itself can lead to a thematic direction and very often it encourages compositional or technical approaches and practices, but what I will do with the sounds I have picked up is ultimately my own decision. By listening and reflecting on the sound material, I can choose parts that work best together according to a compositional plan. This plan may be derived from them, but it may also preexist waiting for the right material to help it be realized. Each project ultimately deals with a specific topic, related to a philosophical, technical, sonic, structural or other concept. This topic will dictate decisions, as elements become integrated into a whole. The notion of relationships stands as the cardinal abstraction that pulls all the individual pieces together.

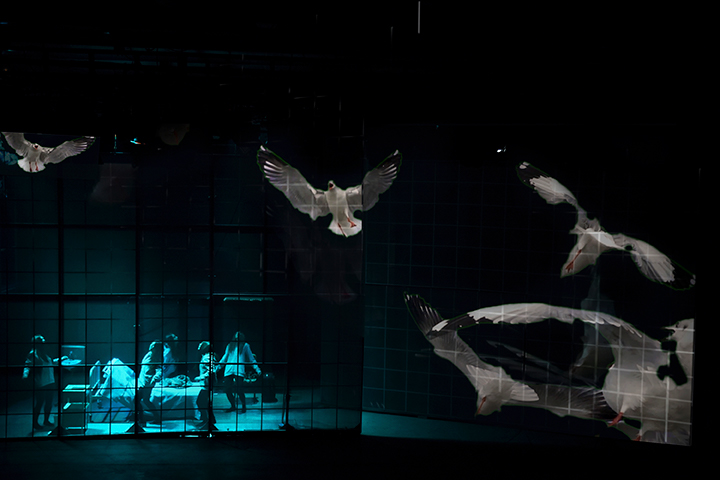

My sonic discourse is an interplay between textures and gestures, energy trends and sonic semiotics, resonances and surprises. Such interplay draws me to the urban soundscape, where it is organically manifested in countless ways. Also, sculpted urban soundscapes exert a particular power on the listener, as do their various transformation processes, subtle or dramatic, progressive or abrupt, laying out an idiosyncratic dream-scape. This evolves and is gradually decoded and interpreted as it oscillates between the known and the unknown through imagination. Within the acousmatic context of my works, the sonic activity alludes to generative processes that seem to be related to a sound origin. But very often these processes have nothing to do with what actually produced the sounds we hear. And the other way around: even the most recognizable of sounds may be integrated into abstract structures, where evolving spectral morphologies create contrapuntal relationships with a flow of evoked connotations, like melodies and harmonies of sonic landscape.

On the other hand, individual sound objects may be considered as abstract, but the manner in which they are presented and linked manages to create an organic, almost tangible reality. They appear, undergo various idiosyncratic changes, follow identifiable energy trajectories, transform spectacularly or tacitly into something else while interacting with their environment, and disappear in various ways. This way, I set the stage for the associations that accompany and enrich the emergent audio perception patterns. Materialization, Particle Chant and Fragmental are based on this idea, abstract sounds that claim materiality by structuring.

As my stylized sonic images participate dynamically in the sonic flow, they shape a musical world of tonal, rhythmic, timbral and spatial structures. So, these pieces do not require a given programmatic or narrative interpretation to achieve their aesthetic function and are proposed as abstract musical creations, with features such as discrete sections, developing densities and dynamics, interplay between transient, patterned and continuous sound elements, tones and noise, repetition and variation, counterpoint, nodal points etc. Any connection with something extra-musical, an object or behavior in the real world, generally unavoidable and mostly welcome, will be multi-layered, subjective, unstable and elusive.

7. Material and strategies

I use strategies that can leverage the characteristics and the musical potential of the city soundscape. For example, although critical auditioning and suitable organizing of collected sounds often makes sense, every recording will not receive the same kind of attention and care. As the amount of city recordings grows freely, the amount of time I spend with each sound notably varies. A sonic scene might be very carefully recorded, but the resulting hours of audio are scanned randomly and arbitrary parts get selected for processing. Under different circumstances, a random and careless recording may later become the subject of intense focus, revealing a wealth of valuable elements after repeated hearings. Certainly, the amount of time and dedication I invest in my sound material relates directly to how deeply I get to understand it, but this does not mean that the creative use of the sounds I encounter and collect demands devoted listening or exhaustive organization.

The urban soundscape is almost too rich. At the very least, I make sure to record things of interest, so I can happily work with them for many hours. Almost no sound will be considered rubbish by default. Even microphone noises or technical errors can be of great interest as material. Inevitably, I will be deleting recordings that I know I don’t need, but audio files don’t take up much space and very often the value of a recording will be assessed later, as work progresses. Some evaluation of the material before creatively engaging with it may seem useful, but if this assertive mindset interferes too much with the creative process, I prefer not to insist. Compositional intent behind a recording certainly gives an evaluation framework, but that won’t stop me from recognizing something interesting beyond the original concept.

With similar logic I approach the issue of isolating sound objects. I do not consider it necessary to separate and classify each recognizable sound based on its spectral characteristics, before I understand exactly what I want to do. I usually keep recorded sound files whole and uncut, with titles that help me remember what and when. Log files help with lengthy and polymorphic recordings. Many times the sequence of recorded events is particularly interesting and of compositional value, so I am in no hurry to break it up. The city soundscape is full of wonderful surprises and coincidences, which I may want to retain intact within phrases. After laying out some material on the montage timeline, I will then isolate individual audio objects and sequences into small or large pieces for further development and use micro-editing and various types of content specific processing to sculpt my sound streams.

The audio material is being sculpted to serve aesthetic or technical needs within the composition. This is done with a wide palette of techniques, ranging from simple cutting to radical transformation. Sometimes recordings are used with little or no processing, as I shape the piece exclusively with cuts, juxtapositions and mixing, playing with connotations and the locally emerging musical narrative. Following an opposite route, I might approach the source recording as a plastic medium that can be transformed at will. This might include heavy processing, mimicking or re-synthesizing recordings and creating a lot more material from one source or a combination of sources.

My composition The Door Study belongs to a series of works with very strict rules regarding the source material, all sounds in the piece stemming from the noise of a door. Working with just one short recording I have the opportunity to systematically research processing techniques and structural approaches. Love Raga, Suvenires and Transference are also examples of this approach, with the material being sourced from electric guitar, a Havana outdoor market and short distorted clips of traffic, respectively. For other projects I may choose sound material freely and incorporate many different sources into a musical whole, following the specific theme. The Way In, The Maze and Chaotic Lucidity are examples of such an approach towards source material selection. In Rites of Passage, in addition to the 24 hour on-site field recording, I used sounds from other cities, synthesizers, and the radio in order to realize my musical narrative.

The composition proceeds with montage, mixing and time-varying processes, both on small and large time scales. I pay close attention to the details of the sound flow, with repeated hearings of moments, phrases or parts and multiple simultaneous adjustments. It is strangely easier to hear the same moment over and over again, trying to adjust something critical, than to listen to a piece from the beginning in order to judge the duration of a large pause somewhere in it. Listening through a range of sound systems and in the presence of other people often helps to complete a project, as does abstaining from that material for some time. Although a piece has to be considered as finished, at some point, I am not against revising older works. A couple of years may be exactly what is needed for a trivial change that will make a big positive difference. Compositions can be seen to mature within an ecosystem of music-making tendencies and creative opportunities, as material and ideas develop and recycle. This is another aspect of my work that connects to the city soundscape: a system of maturing relationships that are being collectively experienced within moving frames, in often chaotic conditions.

8. Final tangents – conclusion

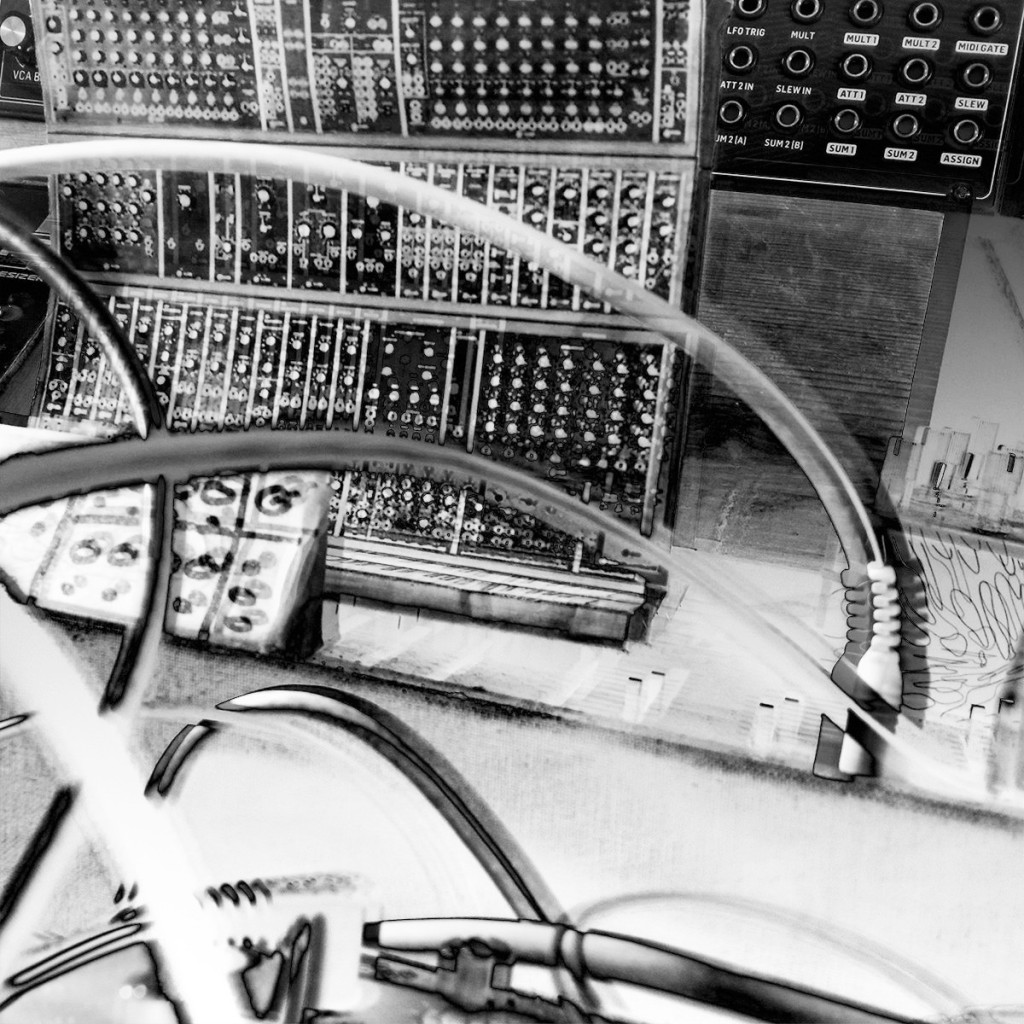

Besides a composer’s/sound collector’s maximalist kaleidoscope, urban sound recording fuels for me an interest in improvisation with real-time sound design techniques. Inspired by the sound of the city and contemporary music tradition, I build devices and applications that allow me to produce and manipulate a variety of sounds, both in the studio and on stage. With these instruments, I can sculpt sound within the creative flow of improvisation or following the instructions of a score. I have used them in works such as Power Toy Fantasy, The Sonic Alchemist and Athens Modular Soundscapes. They are the main part of my setup in solo performances of live electroacoustic music or in projects with other musicians, such as the improvisation ensemble RSLG Quartet. Sounds of the city and methods for their improvised manipulation find also their place in other musical genres that I occasionally work with, such as dub, drum&bass or electro-folk.

With this paper I have attempted to show the connection between urban sound and a composer’s creative outlook. While analyzing my creative affinity to the urban soundscape, I attempted to position my perspective in relation to the concepts of noise, soundscape and field-recording. My conclusion is that the appreciation, creative recording and manipulation of urban sound can grow into a compositional language that connects with relevant musical cannons and works with, recasts, or even transcends, cultural tenets.

I don’t know where my sonic quest will lead me to, or for how long I am going to be living in a big city, enjoying the noise and treasuring semblances of silence. In any case though, the urban soundscape will be playing its own decisive role in the development of musical understanding and practice. And as today’s cars and motorbikes move slowly to the great noise museum, together with the steam locomotive and the typewriter, I will be playing along.

Sound and Multimedia works

Cage, John (1952). 4’33”, Performance by William Marx 2010. https://youtu.be/JTEFKFiXSx4, accessed on 19/10/2021.

Giannoulakis, Stelios (1999). The Way In. https://giannoulakis.bandcamp.com/track/the-way-in, accessed on 19/10/2021.

Giannoulakis, Stelios (2000-2004). The Electroacoustic Gallery.http://giannoulakis.bandcamp.com/album/the-electroacoustic-gallery, accessed on 19/10/2021.

Giannoulakis, Stelios (2007-2010). In Form. http://giannoulakis.bandcamp.com/album/in-form, accessed on 19/10/2021.

Giannoulakis, Stelios (2016-2021). Music for Diffusion. http://soundcloud.com/stgiann/sets/music-for-diffusion, accessed on 19/10/2021.

Giannoulakis, Stelios (2014). Power Toys live performance at ICMC 2014. https://youtu.be/cxcrWcL57V8, accessed on 19/10/2021.

Ikeda Ryoji, (2013). Transfinite, Video Installation at Park Avenue Armory, New York. https://youtu.be/omDK2Cm2mwo, accessed on 19/10/2021.

Kubrick, Stanley (1971). A Clockwork Orange. Feature Film, Warner Bros, Columbia.

Merzbow (1983-1984). Merzbow Life Performance Series Vol. 1-5. ZSF Produkt

Pan Sonic (2001). 05/10/995. CD, Jenny Divers JD099.

Reed, Lou. (1975). Metal Machine Music. 2xLP, RCA Records, RCA: CPL-21101, CPL2-1101.

RSLG Quartet (2015). RSLG live, ImproFest2015. https://www.mixcloud.com/RSLG/rslg-quartet-live-improfest2015, accessed on 19/10/2021.

Russolo, Luigi (1913). Risveglio Di Una Città. Die Kunst Der Geräusche (2000), CD, WERGO T 5142.

Smalley, Dennis (2000). Sources / scenes. CD, Empreintes DIGITALes, IMED 0054.

The Jimi Hendrix Experience (1968). Foxy Lady live at Miami Pop. https://youtu.be/_PVjcIO4MT4, accessed on 19/10/2021.

Vaggione, Horacio (1978). La Maquina De Cantar. LP, Cramps Records 5206 118.

Varese, Edgard (1931). Ionisation, performed by Ensemble Intercontemporain (2012). https://youtu.be/a9mg4KHqRPw, accessed on 19/10/2021.

Wishart, Τrevor (1978). Red Bird (A Political Prisoner’s Dream). LP, York Electronic Studios, YES 7.

Xenakis, Iannis (2002). La Légende D’Eer. CD, Montaigne, MO 782144.

References

Henry David Thoreau, Journal Vol. 1, New York, Houghton Mifflin, 1906, p. 12.

Jeff Todd Titon, “Thoreau’s Ear”, in Sound Studies vol. 1, London, Taylor & Francis, 2015, p. 146.

Luigi Russolo, “The Art of Noises”, 1913, in www.unknown.nu/futurism/noises.html, date of consultation 19/10/2021.

Joseph Nechvatal, Immersion Into Noise, Michigan, Open Humanities Press, 2012, p. 12.

Jacques Attali, Noise: The Political Economy of Music, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1985, p. 23.

Lucy O’Brien, “How We Met: Brian Eno and Tom Phillips”, 1998, in http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/how-we-met-brian-eno-and-tom-phillips-1198029.html, date of consultation 19/10/2021.

Simon Emmerson (ed.), The Language of Electroacoustic Music, 1986, London, Macmillan.

Michael Southworth, “The Sonic Environment of Cities’’, in Environment and Behavior Vol. 1, 1969, p. 49-70.

Bryan Pijanowski et al., “Soundscape Ecology: The Science of Sound in the Landscape”, in BioScience Volume 61:3, 2011, p. 203–216.

Bernie Krause, The Great Animal Orchestra: Finding the Origins of Music in the World’s Wild Places, London, Little Brown Book Group, 2012, p. 278.

ISO/DIS 12913-1, Acoustics. Soundscape – part 1: definition and conceptual framework, Geneva, International Standardization organization, 2014.

Antonella Radicchi, “Sound and the healthy city”, in Cities & Health Vol 5:1-2, 2021, p. 7.

Timothy Ingold, “Against Soundscape”, in Autumn Leaves: Sound and the Environment in Artistic Practice, A. Carlyle (ed.), Paris, Double Entendre, 2007. pp. 10-13.

Raymond Murray Schafer, The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World, New York, Knopf, 1977.

ibid., p. 237-247.

Eleanor Ratcliffe, “Toward a Better Understanding of Pleasant Sounds and Soundscapes in Urban Settings”, in Cities & Health Vol 5, 2019, p. 3.

Torben Sangild, The Aesthetics of Noise, Copenhagen, Datanom, 2002, p. 12.

Raymond Murray Schafer, op. cit., p. 182.

Marie Suzanne Thompson, Beyond Unwanted Sound: Noise, Affect and Aesthetic Moralism, New York, Bloomsbury, 2017.

Marie Suzanne Thompson, op. cit., p. 28.

X. Serra and J. Smith, “Spectral Modeling Synthesis: A Sound Analysis/Synthesis Based on a Deterministic plus Stochastic Decomposition”, in Computer Music Journal Vol. 14, Cambridge MA, MIT Press, p. 12.

Claude Shannon, “A Mathematical Theory of Communication”, in Bell Systems Technical Journal Vol. 27:3, 1948, p. 379.

Marie Suzanne Thompson, op. cit., p. 21.

Suzanne G. Cusick, “Music as Torture / Music as Weapon”, in Transcultural Music Review Article#10, 2006.

Vassilis Raphaelides, Elementary Aesthetics, Athens, Ekdoseis Tou Eikostou Protou, 1992, p. 77.

Paul Hegarty, Noise/Music: a History, London, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2007, p. 3-19.

Marie Suzanne Thompson, op. cit., p. 240.

Hildegard Westerkamp, “The Microphone Ear: Field Recording the Soundscape”, in www.hildegardwesterkamp.ca/writings/writingsby/?post_id=74&title=the-microphone-ear:-field-recording-the-soundscape, date of consultation 19/10/2021.

Jacques Poullin, The Application of Recording Techniques to the Production of New Musical Materials and Forms. Applications to ‘Musique Concrete’, National Research Council of Canada Technical Translation TT-646, translated by D. A. Sinclair from the original in L’Onde Électrique 34, Ottawa, National Research Council of Canada, 1954, p. 282–91.

Vassilis Raphaelides, op. cit., p. 78.

Theodor W. Adorno, Sound Figures, California, Stanford University Press, 1999, p. 140.

Stelios Giannoulakis, “Relationships: Fusion and Dialectic”, 2012, in www.steliosgiannoulakis.wordpress.com/2012/01/25/relationships-fusion-and-dialectic, date of consultation 19/10/2021.

Trevor Wishart, On Sonic Art, Amsterdam, Harwood Academic Publishers, 1998, p. 139.

Stelios Giannoulakis, “Improvisation with circuit bent toys and selected digital processes”, 2015, in www.steliosgiannoulakis.wordpress.com/2015/09/23/improvisation-with-circuit-bent-toys-and-selected-digital-processes, date of consultation 19/10/2021.